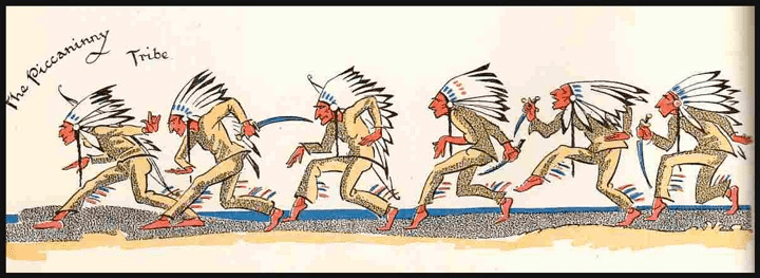

In J. M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy (1911), as Wendy and her brothers, Darlings all, fly to Neverland with Peter and Tinkerbell, on their approach, we hear a “rasping sound that might have been the branches of trees rubbing together”, but, Peter explains, is “the redskins sharpening their knives”. Soon, the author-narrator shows them, “stealing noiselessly down the war path” on the island as they pursue Hook and his pirates:

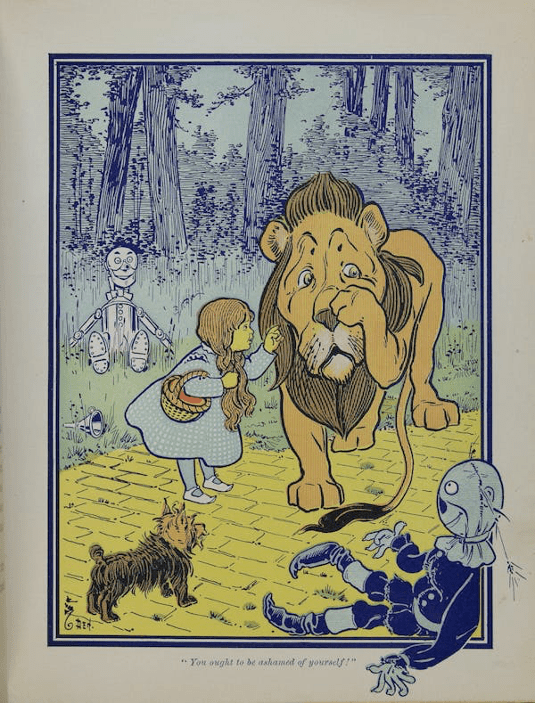

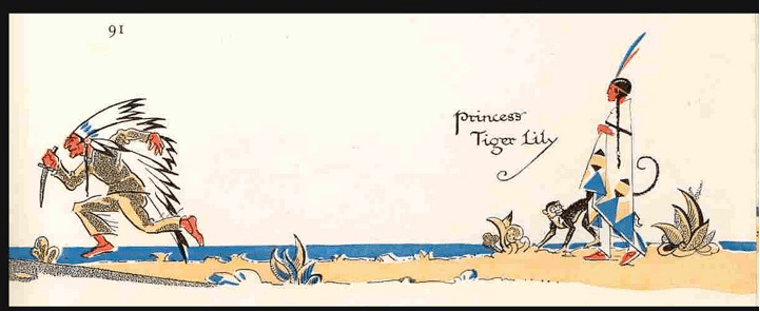

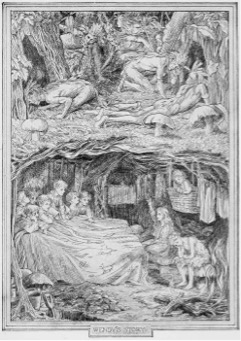

redskins, every one of them with his eyes peeled. They carry tomahawks and knives, and their naked bodies gleam with paint and oil. Strung around them are scalps, of boys as well as of pirates, for these are the Piccaninny tribe, and not to be confused with the softer-hearted Delawares or the Hurons. In the van, on all fours, is Great Big Little Panther, a brave of so many scalps that in his present position they somewhat impede his progress. Bringing up the rear, the place of greatest danger, comes Tiger Lily, proudly erect, a princess in her own right. She is the most beautiful of dusky Dianas and the belle of the Piccaninnies, coquettish, cold and amorous by turns; there is not a brave who would not have the wayward thing to wife, but she staves off the altar with a hatchet. Observe how they pass over fallen twigs without making the slightest noise.

Observe, indeed. And we have to ask, then, just how racist is Peter and Wendy?

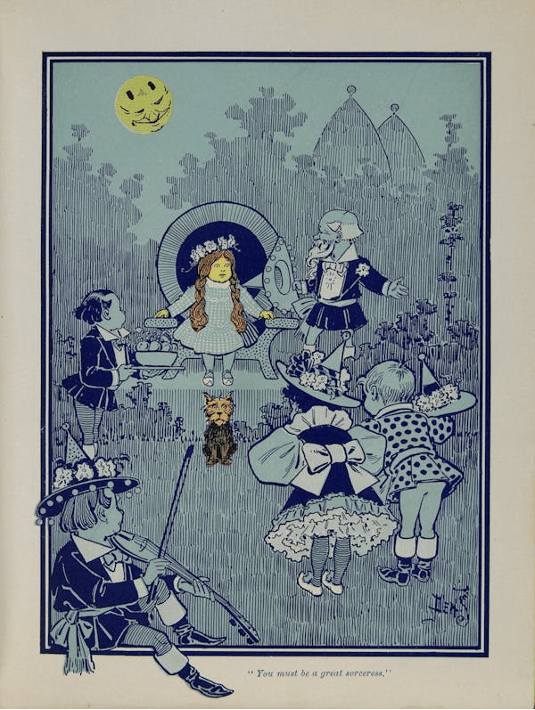

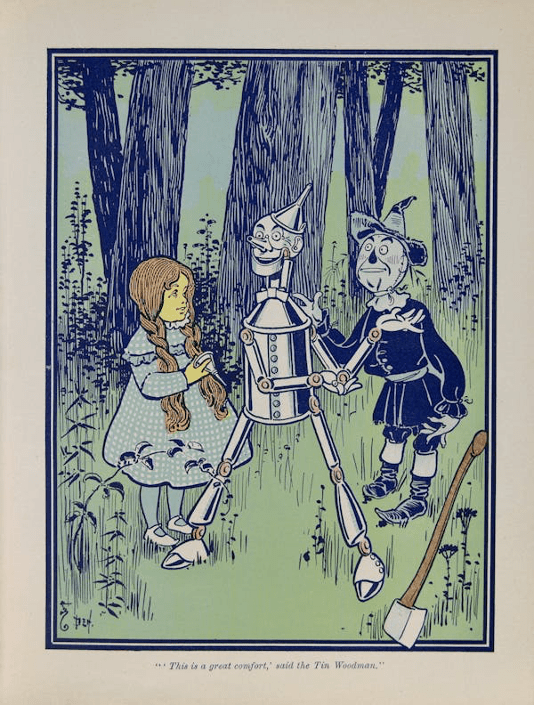

Well, for all it tries to be playful about it, plenty. Beyond all the adventure and performativity in Neverland—some of the island’s groups are reflective, in small part, of the Llewellyn Davies boys (whom Barrie befriended before becoming their guardian) playing roles and games—and the author-narrator’s stabs at humour (with Peter gone, the tribe has fed for six days and are “all a little fat”), the Indians (called “redskin” or “redskins” 35 times) are stereotypically chalk-outlined. They are first shown as: natural and primal (naked, on all fours, making no sound as if moving snakelike); savage warriors (scalping); boasting one noble, mythic, non-white beauty (the Pocahontas-like Tiger Lily is a “dusky Diana” [the warrior-goddess]).

Odder still and even more cringingly, Barrie’s narrator mixes in a farrago of references to pseudo-racialized Others. The tribe is the “Piccaninny,” mainly a term for a black child that was already, by the 1910s, dated and offensive, especially if used by whites (and not just in the U.S. but in the Caribbean, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand). The author-narrator has Tiger Lily speak Chinee English: “‘Me Tiger Lily,’ that lovely creature would reply. ‘Peter Pan save me, me his velly nice friend. Me no let pirates hurt him.’”

But Barrie’s narrator also seems to want to point out and have fun with the stereotypical white-Indian dynamic. He notes that Tiger Lily is “cringing” in her pledge to Peter and that he acts condescending and is happily flattered by the tribe calling him “the Great White Father” and “prostrating themselves before him”, yet the author-narrator basically endorses the idolizing of Peter (cocky though he is). The lost boys, though looked down on by the Indians, play at being Indians. And Wendy’s “private opinion was that the redskins should not call her a squaw” (as if calling a white girl a “squaw” lessens the slur or Wendy should be exempt from stereotypes or another culture seeing her on their terms). The author-narrator acts self-aware about his offensiveness layer-cake so that we can happily eat it, too. He even offers a trying-to-be-funny pseudo-history of white-Indian warfare, but its failures and lapses (italicized by me for emphasis) are obvious:

The pirate attack had been a complete surprise . . . to surprise redskins fairly is beyond the wit of the white man.

By all the unwritten laws of savage warfare it is always the redskin who attacks, and with the wiliness of his race he does it just before the dawn, at which time he knows the courage of the whites to be at its lowest ebb. . . . Through the long black night the savage scouts wriggle, snake-like, among the grass without stirring a blade. The brushwood closes behind them as silently as sand into which a mole has dived. Not a sound is to be heard, save when they give vent to a wonderful imitation of the lonely call of the coyote. The cry is answered by other braves; and some of them do it even better than the coyotes, who are not very good at it. . . .

. . .

The Piccaninnies, on their part, trusted implicitly to [Hook’s] honour, and their whole action of the night stands out in marked contrast to his. They left nothing undone that was consistent with the reputation of their tribe. With that alertness of the senses which is at once the marvel and despair of civilised peoples, they knew that the pirates were on the island from the moment one of them trod on a dry stick; and in an incredibly short space of time the coyote cries began. . . . Everything being thus mapped out with almost diabolical cunning, the main body of the redskins folded their blankets around them, and in the phlegmatic manner that is to them the pearl of manhood squatted above the children’s home, awaiting the cold moment when they should deal pale death.

Here dreaming, though wide-awake, of the exquisite tortures to which they were to put him at break of day, those confiding savages were found by the treacherous Hook. . . .

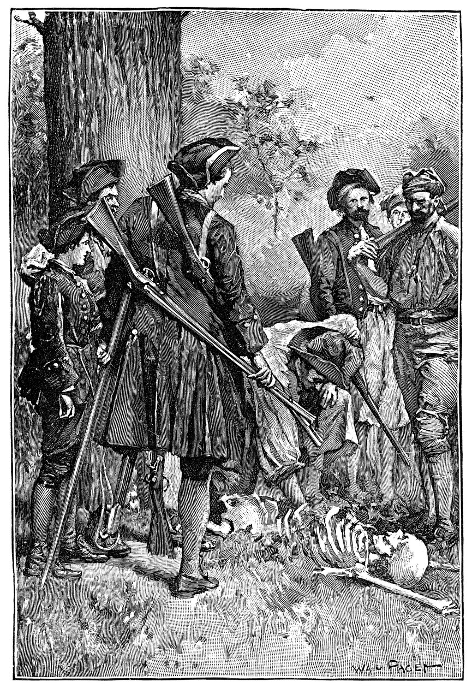

Around the brave Tiger Lily were a dozen of her stoutest warriors, and they suddenly saw the perfidious pirates bearing down upon them. Fell from their eyes then the film through which they had looked at victory. No more would they torture at the stake. For them the happy hunting-grounds now. They knew it; but as their fathers’ sons they acquitted themselves. Even then they had time to gather in a phalanx that would have been hard to break had they risen quickly, but this they were forbidden to do by the traditions of their race. It is written that the noble savage must never express surprise in the presence of the white. Thus terrible as the sudden appearance of the pirates must have been to them, they remained stationary for a moment, not a muscle moving; as if the foe had come by invitation. Then, indeed, the tradition gallantly upheld, they seized their weapons, and the air was torn with the warcry [sic]; but it was now too late.

It is no part of ours to describe what was a massacre rather than a fight. Thus perished many of the flower of the Piccaninny tribe.

So, the author-narrator indulges in a faux-documenting, faux-mythologizing, grandly romantic little History of Hook’s Ambush which endorses condescending-to-Indian adventures. The “redskin” is racially essentialized (e.g., snake-like and innately sneaky). The tribe is too naïve and foolish, undone by their innate (but noble) faith and trust in humanity, and bound to the “tradition of their race”. They are destined to die as doomed, brave warriors, a trope then widespread, with Native Americans seen as stoical and honourable in their extermination, to make the conquerors feel better—they fought a good fight! (though the fight is barely described; the lost boys’ battle with the pirates is detailed much more). The passage is replete with references to the “noble savage” as more natural and primal than animals, while acting self-conscious about it, as if that lets the author-narrator off the hook. But all of it, like so much in Peter and Wendy, is both overdone and undercooked, not-that-funny and trying-too-hard. It is, like so much of the narrative voice in the novel, a bizarre disaster, largely uninteresting for children and frustratingly, fascinatingly bad for adults.

This is an author-narrator, after all, who spinningly turns on his own characters; he says “I despise” Wendy’s mother, calls children “heartless” more than once, is confusing in his use of “we” while acting infantile and petulant (“That is all we are, lookers-on. Nobody really want us.”), envies Peter and, it seems, children, talks over the child reader’s head (even trying to make a joke about the pluperfect!), and offers coyly sexual innuendo about Wendy, Tinkerbell, and Tiger Lily.

So often, the author-narrator seems to be trying to draw attention to himself—as if competing with cocky Peter—and his main mode is, as the critic Barbara Wall has noted, “teasing”. The author-narrator’s racism is as cringing, flippant, and self-indulgent as his tone and voice so often are throughout Peter and Wendy. In trying so hard to be the true Great White Father of the text, he only reveals how pathetically he fails . . . and his failure has echoed on through the years.

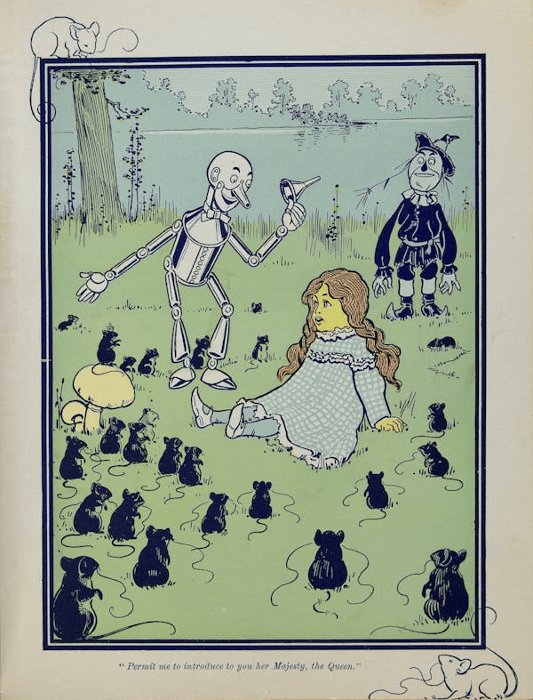

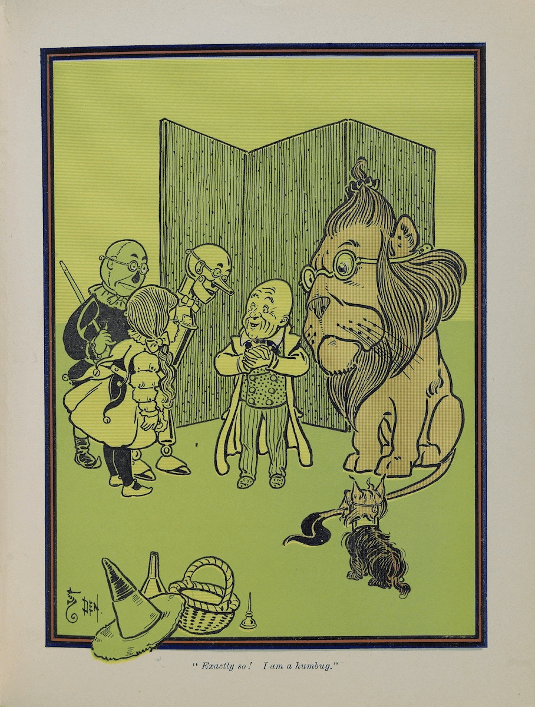

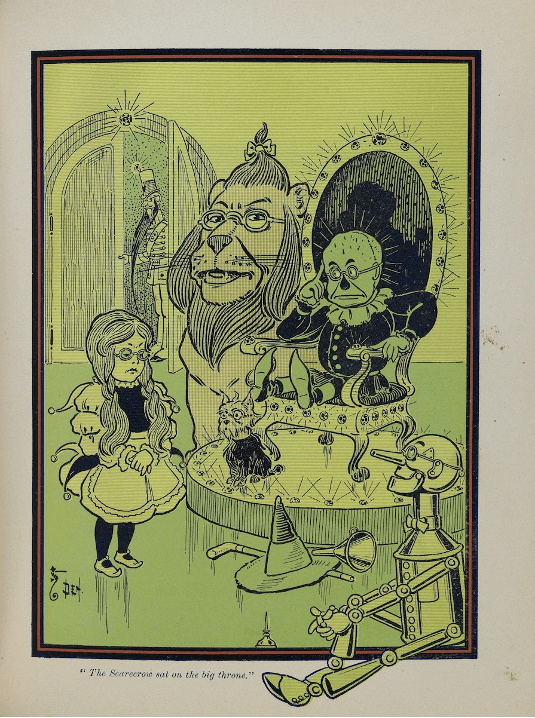

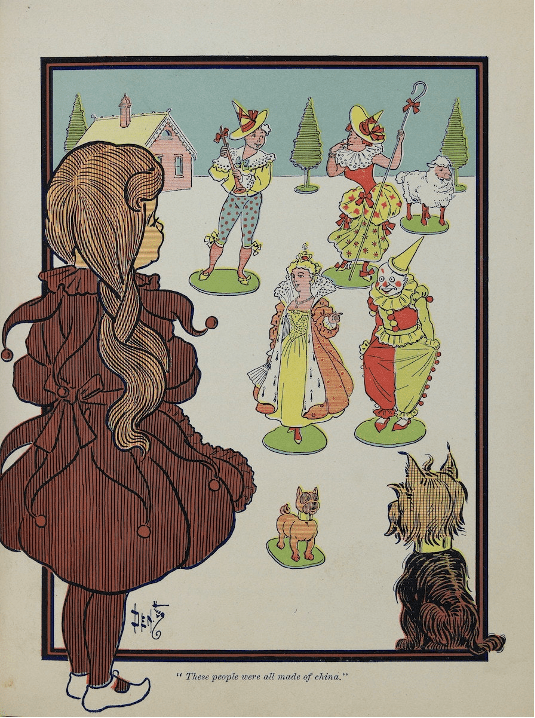

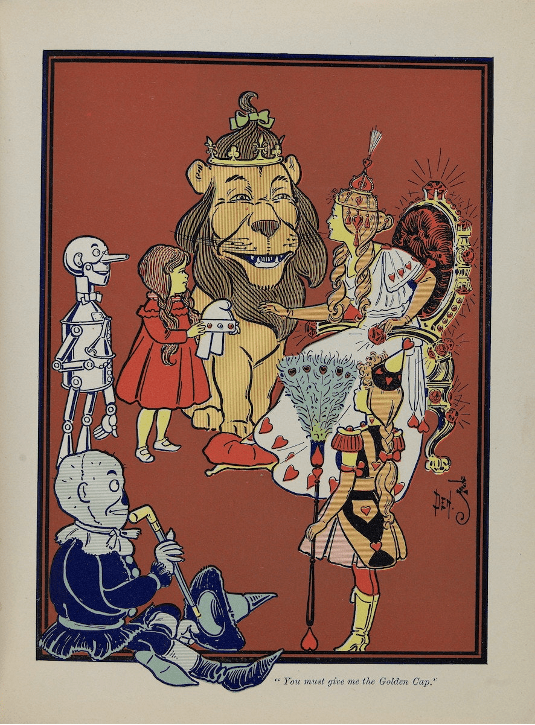

Disney picked up the racism and ran off in a different direction with it in Peter Pan (1953), featuring the song “What Makes The Red Man Red?”, with its Borscht-Belt comic edutainment about the “Injun” as childlike, henpecked, and easily embarrassed: “Once the Injun didn’t know / All the things that he know now / But the Injun, he sure learn a lot / And it’s all from asking, ‘How?’”; “In the Injun book it say / When the first brave married squaw / He gave out with a big ugh / When he saw his Mother-in-Law”; “What made the red man red? / Let’s go back a million years / To the very first Injun prince / He kissed a maid and started to blush / And we’ve all been blushin’ since”. Perry Nodelman has noted the many, many depictions and illustrations of Neverland’s Indians in plays, film adaptations, books, and comic books, including the frequent rendering of Tiger Lily as a notably busty, lighter-skinned object of lust for Peter and the reader. Nodelman decides that “the least dangerous depictions of aboriginals [in the world of Peter Pan] are [those] most obviously offensive [because they are] most playfully obvious about their exaggerated and unrealistic nature [and so] most true to the original”. Yet the obvious conclusion, “true to the original”, is that any depictions of indigenous people in the world of Peter Pan are bound to be—just like the author-narrator’s voice in the source-text Peter and Wendy (the basis of all spinoffs) and its depictions of “redskins”—an abject failure.

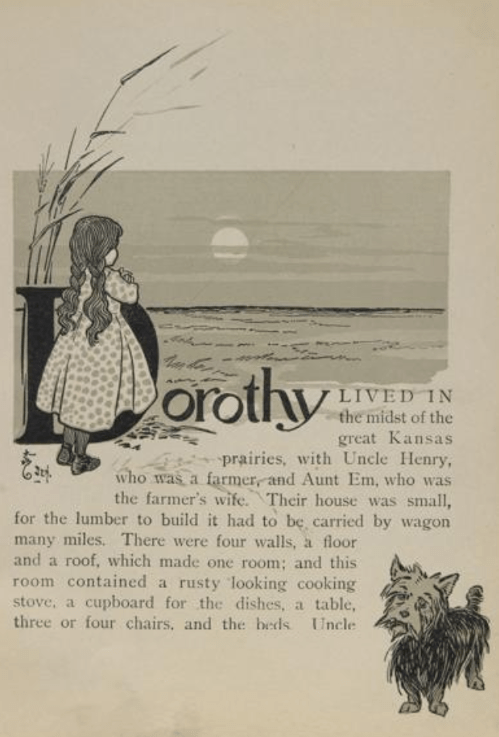

As Jacqueline Rose first recognized and persuasively showed in her excellent criticism of Barrie’s Pan works, which remain some “of the most fragmented and troubled works in the history of children’s fiction”, there is a glaring “problem of writing, of address, and of language, in the history of Peter Pan.” In Peter and Wendy, especially, the line between narrator and characters is muddied, its narrative voice can be contradictory and wayward, she notes, and many of its passages are aberrant. Tiger Lily and her tribe were unlucky enough, and forever doomed, to be both awfully stereotyped and immortalized in the worst “classic” of English children’s literature ever written.

Works Cited and Consulted

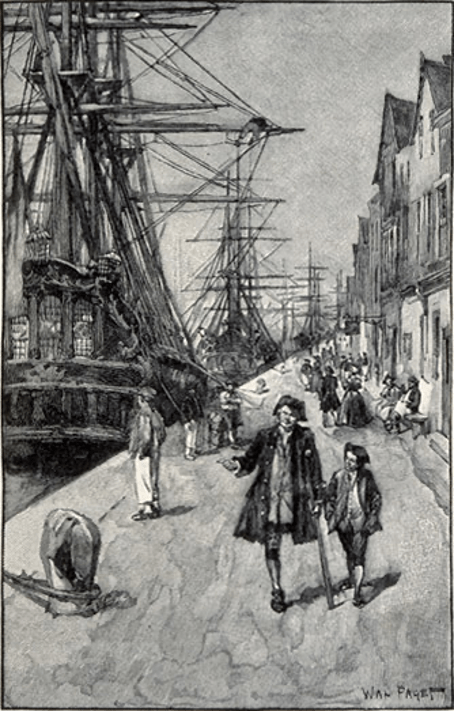

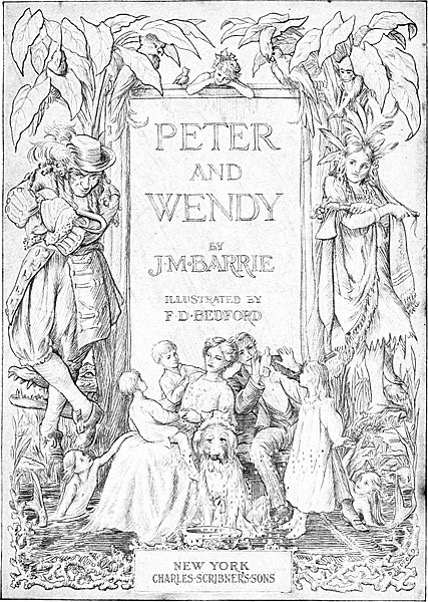

Barrie, J. M. Peter and Wendy. Illustrated by F. D. Bedford. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911.

Nodelman, Perry. “Neverland and Our Land: Imagining Indigenous Peoples in the World of Peter Pan.” Perry Nodelman, n.d. [2019?], https://perrynodelman.com/neverland-and-our-land/.

“piccaninny, n.” Oxford English Dictionary, https://www.oed.com/dictionary/piccaninny_n.

Rose, Jacqueline. The Case of Peter Pan or The Impossibility of Children’s Fiction. Macmillan, 1984.

Wall, Barbara. The Narrator’s Voice: The Dilemma of Children’s Fiction. St. Martin’s, 1991.

The author, a professor of literature, has written and published this blog post for educational, critical, and analytical purposes. All images are included only to bolster the post’s argument and to further its educational purpose.