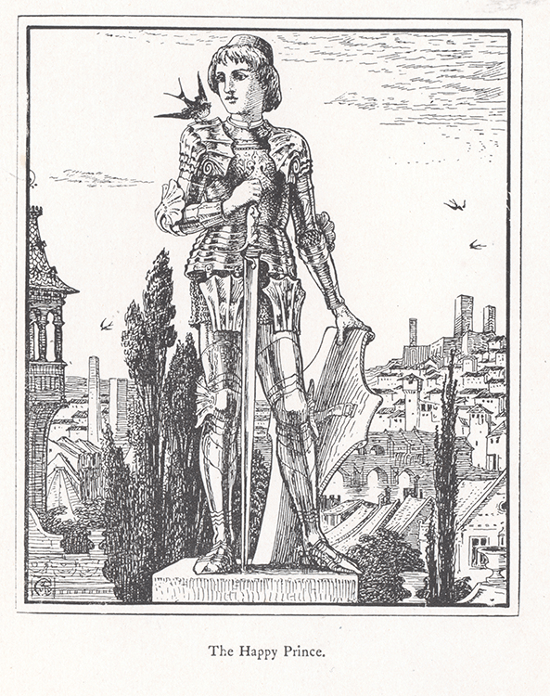

Oscar Wilde’s “The Happy Prince” (1888) is an Andersen-esque bedtime story that’s poetic, wryly humorous, richly melancholic, and playfully aestheticist (surface leads to depth: the statue of the Prince has the Swallow strip away his surface to substantively help those in need; the acts of sacrifice deepen the bond between the two). It’s deeply compassionate about the poor (when, some estimates have it, more than 25% of England was living in poverty) and slyly radical in its politics (socialist, anti-utilitarian, and homosocial). But it’s also, in one glaring blemish of a way, sadly conventional, even reactionary, for its time. Wilde is guilty, in his fable, of blatant anti-Semitism.

By the late 1800s, religious anti-Judaism had morphed into racial anti-Semitism (a term first used in the 1870s). Todd M. Endelman notes that, “in novels, newspapers, and the theatre, malicious or crude images of Jews were common fare. Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray, and Anthony Trollope, as well as dozens of less talented scribblers, unhesitatingly incorporated grasping, lisping Jews into their fiction and journalism.” But Jew-hatred in Victorian England only got pronounced, it seems, with the migration, from the 1880s to the 1910s, of 120,000 to 150,000 Eastern European Jews to England in the wake of Russian pogroms and other persecutions on the continent.

In Wilde’s story, as the Swallow flies with a ruby (from the Prince’s sword-hilt) to give to a poor seamstress (with a sick child), embroidering a gown for an ignorant, cruel Queen’s maid-of-honour (like so many at the time, she thinks of the poor as lazy), he “passed over the Ghetto, and saw the old Jews bargaining with each other, and weighing out money in copper scales. At last he came to the poor house and looked in. The boy was tossing feverishly on his bed, and the mother had fallen asleep, she was so tired.” And so the Jews, self-involved and utterly uncaring about the poor, are associated only with money and graspingly, greedily holding onto it.

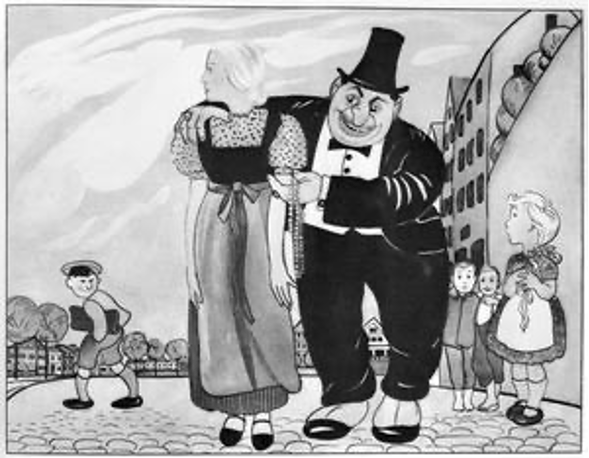

And it got worse. A few years later, in The Picture of Dorian Gray, Wilde offered up even more vile anti-Semitism with the figure of a theatre manager, defined by Dorian Gray for Lord Henry by his Jewishness (e.g., “The Jew manager”) and not his name or character: “‘A hideous Jew, in the most amazing waistcoat I ever beheld in my life, was standing at the entrance, smoking a vile cigar. He had greasy ringlets, and an enormous diamond blazed in the centre of a soiled shirt. . . . There was something about him, Harry, that amused me. He was such a monster.’” (In some late twentieth-century editions of the novel—e.g., Dell Laurel, Signet—“Jew” is changed to “man”.) The manager, Mr. Isaacs, is much like a fairy-tale ogre from whom Sybil must be rescued by Dorian, “‘Prince Charming’”. Or he is a savage Other, like the beastly creature enslaved by Prospero in The Tempest: “the fat Jew manager who met them at the door was beaming from ear to ear with an oily, tremulous smile. He escorted them to their box with a sort of pompous humility, waving his fat jewelled hands, and talking at the top of his voice. Dorian Gray loathed him more than ever. He felt as if he had come to look for Miranda and had been met by Caliban.”

Of course, by the time Wilde died of cerebral meningitis in Paris, in 1900—after his three infamous trials, his imprisonment and forced labour, his destitution, and his estrangement from his family—his name and works had become anathema to the public, so associated were they with homosexuality and degeneracy. And so that greater, Wilde-focussed public prejudice blotted out whatever pernicious influence the anti-Semitism in “The Happy Prince” and The Picture of Dorian Gray may have had. But modern anti-Semitism, particularly across Europe, helped bring the Nazis to power in Germany and led to the Holocaust. And Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wilde, though born into a Protestant family, must have been all too aware, growing up in Ireland, of how insidious, nasty, and dangerously effective prejudice against a group of people—reduced and demonized—could be. Sadly, he forgot that lesson in one of his (otherwise) great children’s stories.

Works Cited

Endelman, Todd M. The Jews of Britain: 1656-2000. U of California P, 2002.

Wilde, Oscar. “The Happy Prince.” 1888.

—. The Picture of Dorian Gray. 1891.

The author, a professor of literature, has written and published this blog post for educational, critical, and analytical purposes. All images are included only to bolster the post’s argument and to further its educational purpose.