In English, “Grimm” seems like a classic case of nominative determinism (I am named, therefore I am). Just riffle through any Brothers Grimm anthology for proof of the German folktale-collectors and -retellers’ grimness. Take “The Stubborn Child” (c. 1819):

Once upon a time there was a stubborn child who never did what its mother told it to do. The dear Lord, therefore, did not look kindly upon the child, and let it become sick. No doctor could cure it and in a short time the child lay on its deathbed. After it was lowered into its grave and covered over with earth, one of its little arms suddenly emerged and reached up into the air. They pushed it back down and covered the earth with fresh earth, but that did not help. The little arm kept popping out. So the child’s mother had to go to the grave herself and smack the little arm with a switch. After she had done that, the arm withdrew, and then, for the first time, the child had peace beneath the earth.

A 139-word distillation of Grim(m)ness, surely! There’s the recalcitrant child, not honouring its mother, and so the harsh Old Testament God neglects it, letting it be taken by illness, only for the still-defiant child, trying to resist our “dear” heavenly Father (not to mention death), needing one final smack by its earthly parent to be put in its resting-place (and so it has “peace beneath the earth,” echoing Luke 2:14: “on earth peace, good will toward men”). The end, happily ever after?!?

Folk tales, told and passed down by common people, communicate a sense of wonder, but the wonder here is an awe-filled affirmation of the power of God and adult authority. Especially to a modern reader, this tale just seems horrifying (and zombie-like). But the Grimms were writing in an age far grimmer than today, with the times unkind to der kinder. Children weren’t only surrounded by death but often taken by it—the infant mortality rate was quite high—and even then, if they lived, many children were abandoned by parents (see “Hansel and Gretel”).

The brothers, Jacob (1785-1863) and Wilhelm (1786-1859), gathered their folk tales and first published them between 1812 and 1815, but, with each edition of their collected stories (seven in all, the last published in 1857), they altered and revised more and more for middle-class respectability, softening and sanitizing by removing suggestions of sex, adding Christian references, emphasizing gender roles more for patriarchal society, and making mothers stepmothers (thus shifting any sense of animus away from biological parents).

So, comparing first version with last, we see how the Grimms’ opening tale in their collection, “The Frog King or Iron Heinrich”—likely from a story told in Kassel’s Wild family (Wilhelm married a woman from the family)—is an “animal-groom” story, about a creature bargaining for a place in the princess’s bed and marriage (“if you’ll love and cherish me”) to her:

| 1812 | 1857 |

| The frog said, “I do not want your pearls, your precious stones, and your clothes, but if you’ll accept me as a companion and let me sit next to you and eat from your plate and sleep in your bed, and if you’ll love and cherish me, then I’ll bring your ball back to you.” | The frog answered, “I do not want your clothes, your pearls and precious stones, nor your golden crown, but if you will love me and accept me as a companion and playmate, and let me sit next to you at your table and eat from your golden plate and drink from your cup and sleep in your bed, if you will promise this to me, then I’ll dive down and bring your golden ball back to you.” |

The animal-groom tale commonly reflects notions of women finding male sexuality ugly, scary, etc. When the frog appears at the palace door, the female’s immediate, outsized fear is remarkable:

Frightened, she slammed the door and returned to the table. The king saw that her heart was pounding and asked, “Why are you afraid?”

| “There is a disgusting frog out there,” she said . . . | . . . “it is a disgusting frog.” |

And it becomes clear—though clearest in the first version—why the princess does not want to let him in. The tale is, most of all, about a young (virgin) woman’s (understandable) fear of penetrative sex and her disgust and repugnance for the male member (implied by the frog in his clamminess and earthiness—more representative of the testicles than the penis). But the unwilling bride’s kingly father, representing the patriarchy and ruling over his daughter, commands her to fulfill her bargain and be with the creature. (In the palace, she hardly speaks, but almost always obeys, made compliant by male authority.) So, after the frog has sat with her and eaten from her plate:

| When he had eaten all he wanted, he said, “Now I am tired and want to sleep. Take me to your room, make your bed, so that we can lie in it together.” The princess was horrified when she heard that. She was afraid of the cold frog and did not dare to even touch him, and yet he was supposed to lie next to her in her bed; she began to cry and didn’t want to at all. There was no helping it; she had to do what her father wanted, but in her heart she was bitterly angry. She picked up the frog with two fingers, carried him to her room, and climbed into bed, but instead of laying him next to herself, she threw him bang! against the wall. “Now you will leave me in peace, you disgusting frog!” But when the frog came down onto the bed, he was a handsome young prince, and he was her dear companion, and she held him in esteem as she had promised, and they fell asleep together with pleasure. | The frog enjoyed his meal, but for her every bite stuck in her throat. Finally he said, “I have eaten all I want and am tired. Now carry me to your room and make your bed so that we can go to sleep.” The princess began to cry and was afraid of the cold frog and did not dare to even touch him, and yet he was supposed to sleep in her beautiful, clean bed. She picked him up with two fingers, carried him upstairs, and set him in a corner. As she was lying in bed, he came creeping up to her and said, “I am tired, and I want to sleep as well as you do. Pick me up or I’ll tell your father.” With that she became bitterly angry and threw him against the wall with all her might. “Now you will have your peace, you disgusting frog!” But when he fell down, he was not a frog, but a prince with beautiful friendly eyes. And he was now, according to her father’s will, her dear companion and husband. He told her how he had been enchanted by a wicked witch, and that she alone could have rescued him from the well, and that tomorrow they would go together to his kingdom. Then they fell asleep. |

The first version makes the princess’s fear of, anger about, refusal of, and then (after crossing the threshold to enter her bedroom) pleased acceptance of sex (once he is so clearly a “handsome young” man), more obvious: “She was afraid of the cold frog and did not dare to even touch him, and yet he was supposed to lie next to her in her bed” –> “she was bitterly angry . . . instead of laying him next to herself, she threw him bang! against the wall” –> “when the frog came down onto the bed” –> “they fell asleep together with pleasure”. But the revisions turn the story away from its original focus on female sexuality, even female sexual pleasure or excitement by the end, and morph it into a story of female revulsion with or repulsion of male sexuality and anxiety about marriage, resolved by patriarchal command: “he was now, according to her father’s will, her dear companion and husband.”

There’s still the fascinating paradox that it’s only when the virgin, commanded to submit, acts on her anger and fear, violently throwing the creature against the wall (trying to kill him?), that he transforms into the man she can accept, sleep with, and love. (Most variations on the story, from different countries, involve the princess being nasty to the frog at first—some even have her beheading the suitor or tearing him, as a snake, in two.)

But the Grimms’ story isn’t over—it’s capped off with “Iron Heinrich”. The commanded princess is, even after her moment of violent refusal, dismissed by the end, which sees the prince reunite with his servant, who “had had three iron bands put round his heart to stop it bursting with grief and sorrow”. In David Luke’s translation, “Faithful Harry” is “full of joy that his master had been saved”. Unlike the princess, who hadn’t wanted to honour her promise, Heinrich/Harry is—embodying loyalty and strength, seen as German values; the Grimms were nationalists—dutiful, duty-bound, and so thankful for his master’s return, so full of love for him, that his three bands crack apart and fall, “because his master was saved and happy”. Thus ends the story, with its true love being the male servant’s love for his master. The patriarchy is upheld; only male-male, class-bound love can be trusted. The end, happily ever after?!?

Works Cited

Ashliman, D. L. “The Frog King or Iron Heinrich by the Brothers Grimm[:] a comparison of the versions of 1812 and 1857.” Folklore and Mythology Electronic Texts, https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/frogking.html, revised 30 Nov. 2005.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. “The Stubborn Child.” c. 1819. Translated by Jack Zipes (with emendations according to the original German, where the neuter was used for the child).

—. “The Frog King, or Iron Harry.” 1857. Selected Tales. 1982. Translated by David Luke, Penguin, 2004, pp. 271-74.

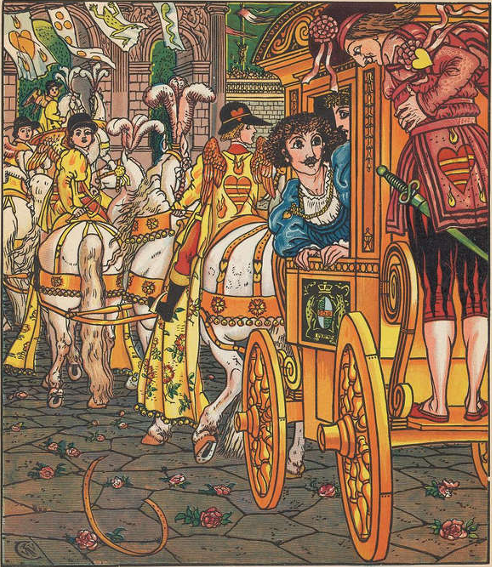

—. The Frog Prince. Illustrated by Walter Crane. George Routledge and Sons, 1874.

Tan, Shaun. The Singing Bones. Arthur A. Levine, 2016.

The author, a professor of literature, has written and published this blog post for educational, critical, and analytical purposes. All images are included only to bolster the post’s argument and to further its educational purpose.