The mirror that Alice goes through into the looking-glass world . . . the wardrobe that Lucy Pevensie enters only to find Narnia . . . Max travelling out of his bedroom to the land of the wild things . . . Tom Long hearing a grandfather clock strike thirteen in the downstairs hall of a building in 1950s Cambridgeshire, then opening the back door to find himself in a vast garden in Victorian England . . .

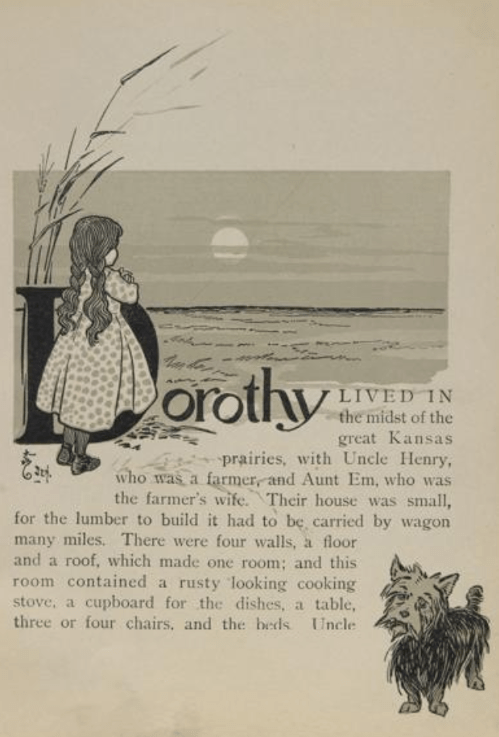

Children’s literature is replete with portals. And Frank L. Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), illustrated by W. W. Denslow, and the basis for the famous 1939 MGM film, is straw-stuffed to its scarecrow-brim with them. A cyclone whisks Dorothy, in her Kansas farmhouse with Toto (drawn by Denslow as a terrier), off on her dream-journey (“Dorothy soon closed her eyes and fell asleep”) to a faraway land. There, a yellow-brick road leads the little girl (about 5 or 6, going by Denslow’s drawings) to meet and join up with the Scarecrow, Tin Woodman, and Lion en route to the Emerald City. In Ch. 10, Dorothy pushes a button to gain entry to a big gate, where a Guardian of the Gates fits them all with green glasses before, with a large gold key, unlocking “another gate, and they all followed him through the portal into the streets of the Emerald City.”

But the book’s true portals are its illustrations for the child reader, enticing them into the world of its “modernized fairy tale” through one window-like picture frame after another, some frames just like show windows, that is, a store’s display windows.

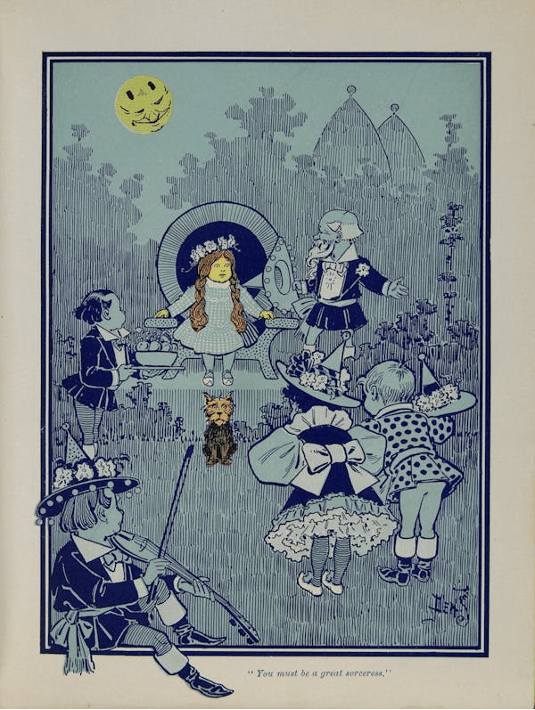

W. W. Denslow’s full-page illustration for “Chapter III How Dorothy saved the Scarecrow.”

Retail and commercialism lie behind so much of Oz. Baum opened and ran a store, Baum’s Bazaar, in Aberdeen, South Dakota (two states north of Kansas), for just over a year; by 1893, he was a travelling glassware and chinaware salesman (Ch. 20 features a land of china) based in Chicago, where the World’s Fair that year showed off so many wares, exhibits, and innovations (the Emerald City seems to be based on the fair’s White City, built in just a year or two; in-between work for the Chicago Herald, Denslow visited the Fair). Then Baum helped customers design show windows, founded and edited The Show Window, a magazine for window decorators, served as secretary of the National Association of Window Trimmers, and published a treatise, The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows and Interiors, in 1900. His title The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is advertisement-like, and, Michael Patrick Hearns notes, it became the “best-selling children’s book of the 1900 Christmas season” and a roaring success—“Baum and Denslow proved that novelty could sell.” In large part, that’s because the book was so resplendent with images, “[w]ith twenty-four color plates and over one hundred textual illustrations in varying colors,” Hearns notes, making it “one of the most lavishly illustrated American children’s books of the twentieth century.”

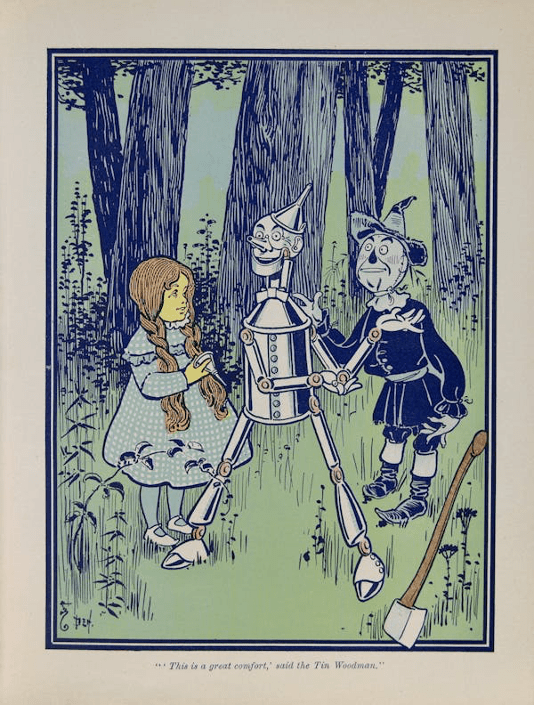

Denslow’s full-page illustration for “Chapter V. The Rescue of the Tin Woodman”.

Denslow’s illustrations, right from the start, act as windows to draw us into the world of the text, echoing how Baum had, as Susan Wolstenholme notes, “turned the [show] window into the stage of a theatre and at the same time an advertising tool.” On the copyright page, for instance, the Tin Woodman is shown just outside the main picture-frame, looking in at the copyright notice tacked onto a tree. The contents page shows the floppy Scarecrow outside the main picture-frame, looking at a piece of paper, and then we see that the main picture, the “List of Chapters”, must be that piece of paper (and so we’ve entered the point-of-view of a character before having met him in the story!). And some of the chapter title-page illustrations or opening pages of chapters (featuring an initial letter) show a character leaning on the picture-frame or looking into the picture.

But it’s with the full-colour plates that Denslow most slyly, splendiferously show-windows us into Oz. (The countries in Oz are associated with different hues, in keeping with colour theory, which Baum explains in The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows and Interiors.) In the land of the Munchkins, its favourite colour blue, we look in at little Dorothy, garlanded and praised as a “‘great sorceress’” by Boq (who’s seen her silver shoes and knows she’s killed the wicked witch of the West), while a Munchkin fiddler, sitting on the picture frame and dangling his leg off it, and other Munchkins all direct our gaze at the girl. Even the man in the moon looks smilingly down on our heroine. (Toto, though, just looks shocked and overwhelmed.) Next, when Dorothy meets the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman, the latter’s axe is leaning against the bottom right corner of the frame, making it all the more obvious that we are looking in on this world, granted a privileged view by image and text.

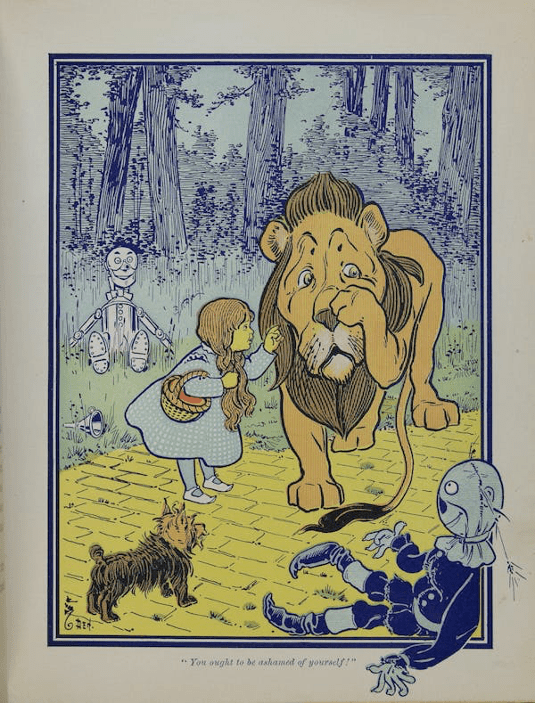

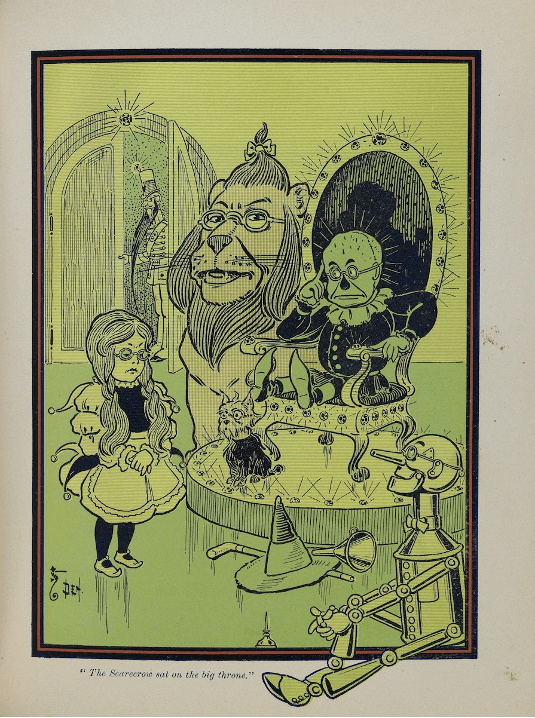

Denslow’s full-page illustration for “Chapter VI. The Cowardly Lion.”

And when Dorothy scolds the Lion, the smiling Scarecrow is floppily nestled, like a doll, in the bottom right corner of the frame, his left arm and hand dangling out, along with some of his head, and we can almost imagine plucking that long, stray piece of straw sticking out of the seam in his sack-like noggin.

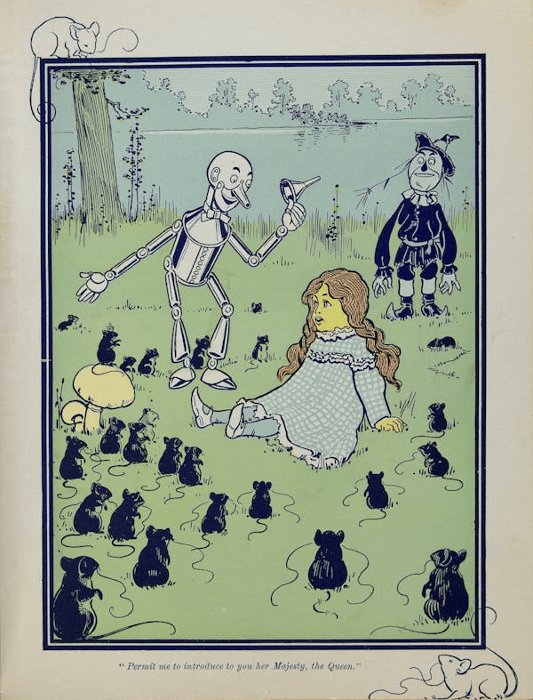

Denslow’s full-page illustration for “Chapter IX. The Queen of the Field Mice.”

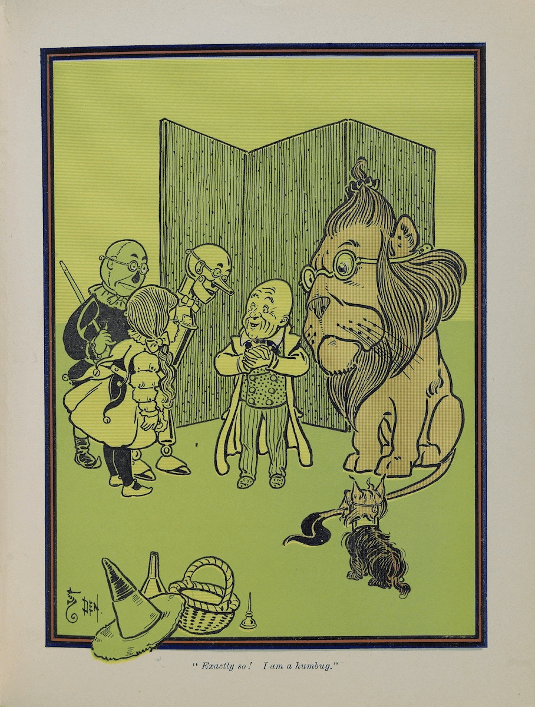

As we look in on Dorothy being presented to the Queen of the Field Mice by a smiling Tin Woodman, doffing his oil-can hat, all the mice in the frame drawing our gaze towards Dorothy, we notice that two mice, in outline, are outside the frame, as if in our (less substantial?) world, looking in, too. And a witch’s hat is partly out of the frame as we look in on the Wizard, in the Emerald City, cheerily admitting he’s a humbug, while the bespectacled quartet (plus a bespectacled Toto) peer askance at him, too. We soon look in on a very different throne-room moment, post-Wizard-departure, when the Scarecrow’s sitting in the high seat and thinking hard while his friends do, too, the Tin Woodman leaning back in contemplation in the bottom right corner of the frame, his legs bent or stretched metallically off the sill, bridging Oz’s world and our world.

Denslow’s full-page illustration for “Chapter XV. The Discovery of OZ, The Terrible.”

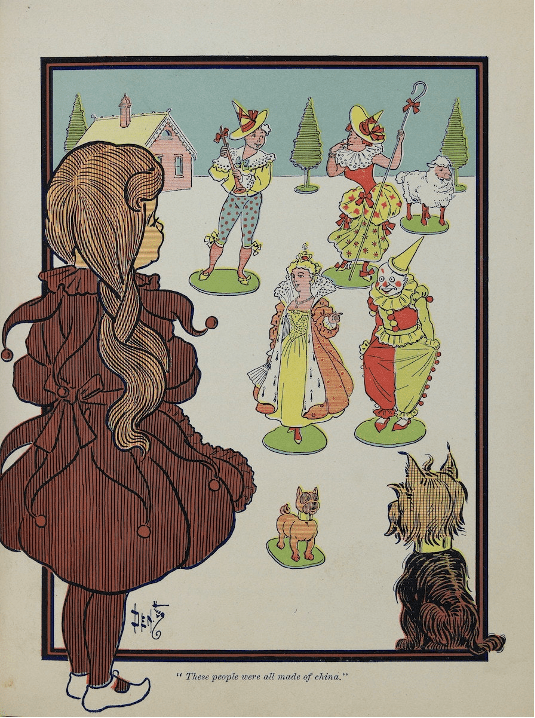

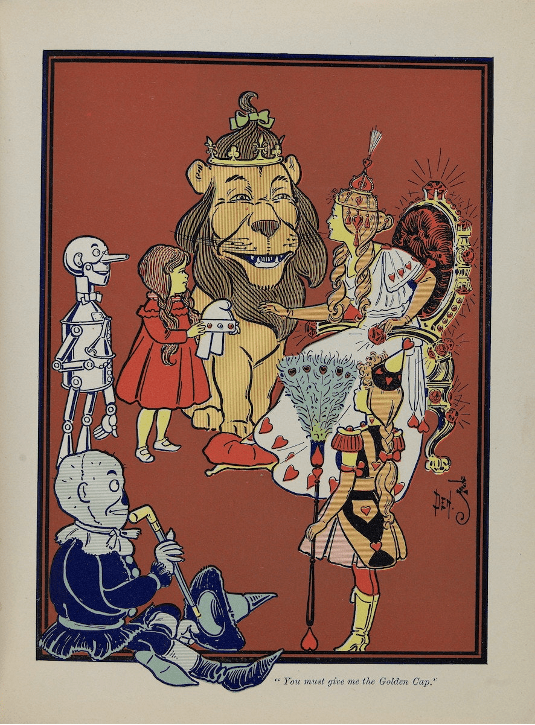

Then there is the world-within-a-world of the “dainty china country”, full of porcelain figurines, and a place so curious and strange that the larger, more powerful Dorothy and Toto stand just outside the frame, as if with us, looking in at these fragile little creatures (including a wee china dog staring eerily at his non-china counterpart). And, finally, in the red of Quadling Country, the Good Witch of the South, Glinda, gets the Golden Cap from Dorothy as her pals look on, the Scarecrow doing so while lying in the bottom left corner of the frame, his right leg and left foot (crossed underneath him) outside the picture. Again and again, then, the child reader feels as if they are right there, on the threshold, staring in, and can just step into the picture with the aid of the magical text of the story. The text itself, in decorative initials with Denslow’s illustrations around them, becomes a part of the world at the start of each chapter.

Denslow’s full-page illustration for “Chapter XVIII. Away to the South.”

In that story-world, though, the Wizard reveals himself to be an actor, magician, showman and, basically, conman—he’s used acting and props (a great Head, a lovely Lady, a terrible Beast, a Ball of Fire) to wow Dorothy and her pals and convince them to kill the Wicked Witch of the West (benefitting him) before they can gain their desires (returning home, a brain, a heart, and courage). He’s a kind of sham salesman. Stuart Culver argues that all relations in the book are commodity relations and the characters are like mannequins meant to stimulate consumer desire in “a gaudy, artificial fantasy world”. Are the show-window illustrations only adding to, even promoting, a sense of show, consumerism, and artifice? As Culver argues, are we readers being asked to be customers and buy false images and idols but never achieve the genuine identities we’re striving for in our consumption? Does Dorothy’s return to grey Kansas suggest, as Wolstenholme argues, that although “the world of the show window glitters with attraction, finally the consumer must go home”? Is the book suggesting that buying is a hollow substitute for home truths and family love (after all, Dorothy wants to return to Kansas, where, when she does, Aunt Em “cover[s] her face with kisses”)? Or implying that an imaginative, showy entertainment can be a harmless detour which only makes the beaten track more delightful to get back to? Or recognizing an emptiness at the heart of capitalism?

Denslow’s full-page illustration for “Chapter XX. The Dainty China Country.”

Intriguingly, the Wizard excuses his years of ruling through façades, fakery, and showmanship thus: “‘How can I help being a humbug,’ he said, ‘when all these people make me do things that everybody knows can’t be done? It was easy to make the Scarecrow and the Lion and the Woodman happy, because they imagined I could do anything.’” Is this a comment on how consumers, like readers, want to be deceived, and how citizens want to be led by an illusion?

Denslow’s full-page illustration for “Chapter XXIII. The Good Witch Grants Dorothy’s Wish.”

Certainly, all the emphasis on show, display, and (bright-coloured) spectacle, with its shop window-like illustrations the most important portal of all, make The Wonderful Wizard of Oz a quintessentially American book. And both Baum and Denslow would cash in and spin off. The pair, co-copyright holders, co-produced an adult-aimed “Musical Extravaganza” version of the book for the stage (notably, a few of Denslow’s Oz illustrations show characters dancing, prancing, or in a chorus-line formation) before they fell out after a dispute over royalties. Baum planned an Oz theme park (never built), wrote thirteen more Oz books, and moved to Hollywood in 1910, where he called his home “Ozcot” and founded The Oz Film Manufacturing Company in 1914 (it made three Oz films). Denslow published Denslow’s Scarecrow and The Tin-Man (1904), newspaper comic pages featuring the two characters, and bought a Bermuda island, naming himself King Denslow I. But he drank his money away, dying of pneumonia in a New York City hospital after a bender paid for by his $250 sale of a cover-illustration for a July 1915 issue of Life.

Works Cited and Consulted

Baum, Frank L. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. 1900. Edited by Susan Wolstenholme, Oxford UP, 2000.

Culver, Stuart. “What Manikins Want: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows.” Representations, no. 21, Winter 1988, pp. 97-116.

Denslow, W. W., illustrator. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. George M. Hill, 1900.

Hearn, Michael Patrick, editor. The Annotated Wizard of Oz. W. W. Norton, 2000 [Centennial Edition].

Wolstenholme, Susan. Introduction. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, by Frank L. Baum, Oxford UP, 2000, pp. ix-xliii.

The author, a professor of literature, has written and published this blog post for educational, critical, and analytical purposes. All images are included only to bolster the post’s argument and to further its educational purpose.