“the first pilgrim called was . . . the fittest”

—the narrator, of Beth’s imminent death, in Little Women

“The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” So begins L. P. Hartley’s The Go-Betweens (1953), but those words apply only too well to a deeply mid-nineteenth-century American book, Little Women (1868-69), brought to life on screen for nearly every new generation since the Gilded Age, with film versions in 1918, 1933, 1949, 1994, and 2019. (Of course, big-screen historical dramas and literary adaptations tend to reflect their own times.) Louisa May Alcott’s two-volume saga of the March sisters (published as Little Women and Good Wives in the UK) and their mother (“Marmee” to her girls) is most decidedly of its place and time—the volumes are set in a small Massachusetts town in 1861/62 and 1866-67—in four ways that seem curious, odd, and even discomfiting now.

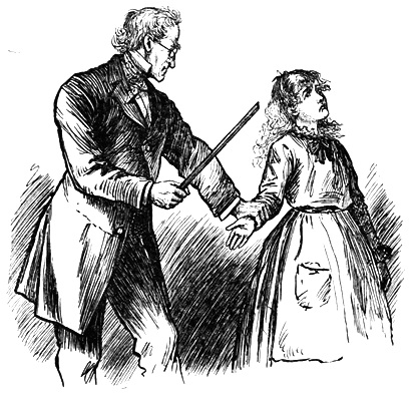

The first is the caning of Amy at school, in the chapter “Amy’s Valley of Humiliation” (one of many references to John Bunyan’s 1678 Christian allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress, important to Alcott’s father and a book he passed on to his daughters). The blonde, youngest March sister is caught with pickled limes by her teacher, Mr. Davis, who rather favours Amy but “had declared limes a contraband article.” (Each March sister has her burden[s] to overcome and eventually embodies an ideal of nineteenth-century American Protestant womanhood; Amy’s burdens are selfishness and materialism, and she comes to represent piety.) Mr. Davis takes the ruler to Amy, then makes her stand before the class until recess. Amy, vowing to not return, goes home, where an “indignation meeting” is held. Jo delivers a letter from their mother to Mr. Davis; Mrs. March, disapproving of corporal punishment, Mr. Davis’s teaching, and of the girls with whom Amy is consorting, says that Amy will study with Beth (and Mrs. March will “‘ask your father’s advice before I send you anywhere else’”). So far, so understandable (and remarkably patriarchal—Mr. March is off at war!). But then Mrs. March tells Amy, “‘I am not sorry you lost [the limes], for you broke the rules, and deserved some punishment for disobedience.’” She continues, “‘I should not have chosen that way [standing in disgrace before the class] of mending a fault . . . but I’m not sure that it won’t do you more good than a milder method. You are getting to be altogether too conceited and important, my dear, and it is quite time you set about correcting it. . . . conceit spoils the finest genius. . . . the consciousness of possessing and using [talent] well should satisfy, and the great charm of all power is modesty.’” Humiliation is turned by the matriarch into a necessary humbling; the wrongness of corporal punishment is righted and rewritten into a homily and lesson about the Christian virtue of humility. And so, in Alcott’s constantly educative book, family provides the best education of all—Amy does not need the institution of school.

(Drawing by Frank T. Merrill for the first illustrated edition [1880] of Little Women)

(In the 1994 film, Amy’s victimization is emphasized, with Mr. Davis made a sexist brute. The caning isn’t shown but Amy [Kirsten Dunst] is afterwards, crying and telling Jo [Winona Ryder] outside their wealthy aunt’s house, “Teacher struck me.” Then, with all gathered in the kitchen as loyal servant Hannah bathes Amy’s wealed hand, Amy explains what happened while Marmee [Susan Sarandon] and Jo pace angrily about; Amy notes, “Mr. Davis said it was as useful to educate a woman as to educate a female cat.”)

(In the 2019 film, Amy’s punishment is a means for drawing the Marches together, hinting at romance, and emphasizing female creativity. The aspiring artist, to gain more limes from and have her lime-debt erased by a classmate, caricatures Mr. Davis on her slate and is caught. [This reworks a moment in the book, when Amy recalls Mr. Davis catching and punishing a classmate who had caricatured him.] Cut to a tutored Laurie [Timothee Chalamet] finding Amy [Florence Pugh] outside the Laurences’ house, wailing. She comes in, acts the lady in the library, charming Laurie [hinting at their romance and marriage]; Meg [Emma Watson] arrives, catching the eye of tutor Mr. Brooke [hinting at their marriage]; Jo [Saoirse Ronan]—her writing career is the film’s focus—arrives to marvel at the books; Marmee [Laura Dern] arrives, telling Amy that she will take her out of school, and Jo will teach her.)

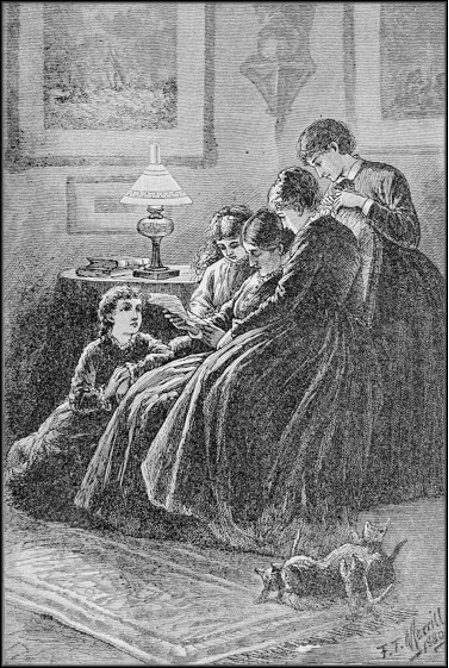

(Drawing by Frank T. Merrill for the first illustrated edition [1880] of Little Women)

The second is the attitude of Little Women to alcohol. After Meg (burdens: vanity and disdain for housework; comes to represent purity and learns to value the home) gets drunk on champagne at a party, and Jo is “‘glad you [Laurie] were not in the saloon, because I hope you never go to such places’”, Meg, at her wedding, notes to Laurie, now in his late teens, that her father only thinks wine should be for the ill, while her mother “‘says that neither she nor her daughters will ever offer it to any young man under her roof.’” Laurie then promises the newlywed Mrs. Brooke and Jo that he will be abstemious, “for which,” the narrator notes, “he thanked them all his life”. Thus the book, implying that alcohol is irreligious, makes its pro-temperance stance.

Abstinence-pledging groups, in which women were prominent, had begun in the 1840s. Temperance, largely a Protestant and rural (and anti-urban) crusade, was soon led by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the male Anti-Saloon League, and associated alcohol with sinfulness. (It all culminated, of course, in Prohibition.) But temperance was also a means of talking (indirectly) about and fighting abuse and marital rape in the home. Working-class and immigrant populations, though, were targeted; Irish and Italians, especially, and other cultures where alcohol was important were hurt by liquor bans and “dry” campaigns. Anti-Irishness is played for laughs in Little Women with Beth’s meant-to-be-comic portrait of a poor, hungry Irishwoman getting a fish from Mr. Laurence (“‘Oh, she did look so funny, hugging the big, slippery fish, and hoping Mr. Laurence’s bed in heaven would be “aisy.”’”) and the narrator’s meant-to-be-comic listing of some rural creatures: “Laurie [threw] up his hat and [caught] it again, to the great delight of two ducks, four cats, five hens, and half a dozen Irish children”.

(In the 1994 film, drinking is turned into a criticism of the patriarchy. Laurie [Christian Bale] makes no promise of abstinence at Meg’s wedding, but he does see Meg [Trini Alvarado], at a ball in Boston, vainly going along with a snobby, patrician crowd and drinking champagne, which he takes from her, remarking, “Miss March—I thought your family were temperance people.” Back at home, before bed, Meg asks her mother, “Why is it Laurie may do as he likes, and flirt and tipple champagne, and no-one thinks the less of him?” “Well,” Marmee replies, “I suppose for one practical reason: Laurie is a man, and, as such, he may vote, and hold property, and pursue any profession he pleases. And so he is not so easily demeaned.”)

(In the 2019 film, drinking isn’t looked down on at all—indeed, in Greta Gerwig’s script, as if channeling Gerwig’s whirling, carefree characters in Damsels in Distress or Frances Ha, Meg is described, at the party, as “done up nearly beyond recognition. She’s powdered and corseted and drinking and flirting. In fact, she’s kind of great at it.”)

(Drawing by Frank T. Merrill for the first illustrated edition [1880] of Little Women)

The third is marriage—it needs parents’ approval and needn’t be for love (you wouldn’t know that at all from the 1994 and 2019 film versions), because love can come after it. In Alcott’s book, Mrs. March tells Jo of how John Brooke, Laurie’s tutor, talked to her and her husband about his love for Meg: “‘He only wanted our leave to love her and work for her, and the right to make her love him if he could’” (my emphasis). And the narrator discloses to us the matriarch’s final words to herself in that chapter, “Confidential”, as if they are a tender aside to the reader: “Mrs. March said, with a mixture of satisfaction and regret, ‘She does not love John yet, but will soon learn to.’” (Those final words would sound ominous today in a sci-fi or horror movie.) And, later, Mrs. March is relieved to hear that Jo doesn’t love Laurie “‘anything more’” than she always has—that is, as a dear friend—because, she says, “‘I don’t think you suited to one another. . . . I fear you would both rebel if you were mated for life. You are too much alike, and too fond of freedom, not to mention hot tempers and strong wills, to get on happily together, in a relation which needs infinite patience and forbearance, as well as love.’” Then Jo says of Laurie, to Beth, “‘Amy is left for him’”! It’s as if one of the eligible sisters, so much of a March-ness, will do for Laurie. Laurie even explains to Jo (burdens: anger and dislike for womanhood; comes to represent feminine decorum) his marriage to Amy thus: “‘Amy and you change places in my heart, that’s all’.” (Imagine any newlywed man saying that today to his sister-in-law!)

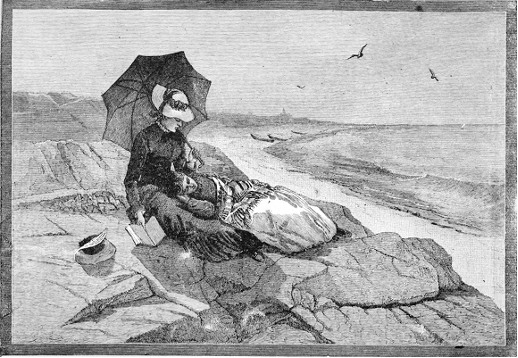

(Drawing by Frank T. Merrill for the first illustrated edition [1880] of Little Women)

The fourth is Beth’s death, which is really not so sad, because of the family’s faith and because the death is so spiritually transfiguring for another sister. Beth, whose burden is shyness, comes to represent submissiveness—to fate, to death, and so to God. She is the March sister who embodies meekness, too, and is that ideal nineteenth-century “angel in the house”—a term even used to describe her. And Beth is Exhibit B of the nineteenth-century literary trope of the holy child dying (made most famous by Dickens, with the death of Little Nell), a sentimental tradition that transforms Jo, the sister most devoted to her, marking the death of her girlhood. We know that Beth’s death is not all that sad, but preordained—part of the author’s (and God’s?) plan—because it’s foreshadowed in Chapter 4, “Burdens”: “There are many Beths in the world, shy and quiet, sitting in corners till needed, and living for others so cheerfully, that no one sees the sacrifices till the little cricket on the hearth [an allusion to Dickens] stops chirping, and the sweet, sunshiny presence vanishes, leaving silence and shadow behind.”

(Drawing by Frank T. Merrill for the first illustrated edition [1880] of Little Women)

In a book rife with lessons, Jo learns patience, charity, loyalty, and faith from Beth’s death, and pledges herself to a better ambition—immortal love, for God. As her younger sister nears the end of her seventeen years on earth, Jo pens a poem, “My Beth”, in which she calls Beth that “‘serene and saintly presence’” who “‘Sanctifies’” the “‘home’”, asks to be given some of her courage and unselfishness, which will make “‘our parting daily loseth / Something of its bitter pain’”, hopes that grief will make her “‘wild nature more serene’”, and looks ahead to renewed “‘Hope and faith, born of my sorrow’”, with Beth’s death thus showing the way to “‘home’”, that is, Heaven. (Perhaps it is altogether too poetic that “Beth” rhymes with . . .) Death is beautiful in that it brings you to God. The narrator tells us, after noting how “a bird sang blithely on a budding bough . . . the snow-drops blossomed freshly at the window, and the spring sunshine streamed in like a benediction over the placid face upon the pillow”, that Mrs. March, Meg, Jo, and Amy “thanked God that Beth was well at last”—it marks an end to her earthly suffering. Beth’s death—at a time when so many American children died young—is so much of a religiously-understood departure and comfort (and not, by today’s standards, a grief-filled tragedy or loss not-to-be-gotten-over) that Amy’s acceptance of Laurie’s proposal comes just a dozen pages after it, at the end of the next chapter, “Learning To Forget”. Even on the second-last page of the book, when we learn that Laurie and Amy’s one girl (called, yes, Beth!) may die young, the narrator tells us that, should she, it will only bring them closer: “the shadow over Amy’s sunshine . . . was doing much for both father and mother, for one love and sorrow bound them closely together.” Not only is death never the end, but it offers, for those who remain, betterment and renewal.

(Drawing by Frank T. Merrill for the first illustrated edition [1880] of Little Women)

(In the 1994 film, Beth’s death is a simple tearjerker, its staged and secular sadness sanctifying Jo. Marmee sobs after telling Jo that Beth [Claire Danes], pallid and propped up on pillows, has, she thinks, “been waiting for you.” Mother and daughter embrace; cut to Beth, eyes shining happily as Jo feeds her broth, then seeming better as Jo performs a reading for her. Yet Beth, voice cracking, diminishes herself and raises Jo up: “I never saw myself as anything much. I’m not a great writer, like you . . . you will be [a great writer]. . . . I can be brave, like you. But I know I’ll be homesick for you, even in heaven.” Then, when Jo shuts the window and looks out at the howling wind and the trees, the music swells, she turns, and her sister has died. The next morning, Hannah drops petals on Beth’s empty bed and her dolls. There is no sense of Beth going to heaven. When Jo asks, in the very next scene, “Will we never all be together again?”, there is no answer from her mother or father, dressed in black. There is only silence in the house.)

(In the 2019 film, Beth’s death is all about Jo’s loss and memory, burnished by shots and cuts, sanctifying cinema itself. In a flashback, Jo remembers lying in bed with a gravely ill Beth [Eliza Scanlen] and telling her to “please fight”, then waking up to come downstairs and find her all better; another flashback, sun-lit, recalls Mr. March coming home from the war. But then, in the present, amid blues and greys, Jo comes downstairs to find Marmee crying and Beth not at the table—Marmee is so distraught that she reaches out for and presses herself into Jo, and it is the child who holds the parent. There’s no sense of God; no words console. The next scene, also wordless, begins with a long shot of Mr. and Mrs. March, Jo, Meg, and a few others standing by Beth’s grave, in the woods, and ends with a close-up of Jo, just staring down; cut to a flashback where Jo’s looking at Beth, decorating outside the home for Meg’s wedding. And so, better than Jo the writer could do [as grief is shown to be beyond words], Gerwig the auteur’s film—with its flashbacks and crosscuts—finds comfort and sadness . . . in secular, cinematic memory.)

Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women is a domestic story that is, in the end and in all of its characters’ endings, earnestly sunny, for it believes in a home after ours, one where the “Heavenly Father”, as Marmee tells her girls, has such “strength and tenderness”. All the “little women” are married off, including Beth, as she is bound to die and so be with that “Friend who welcomes every child with a love stronger than that of any father, tenderer than that of any mother.” Marmee tells Jo that, after loving those here among us, “‘the best lover of all comes to give you your reward.’” Today, perhaps only a Christian film-industry production could offer an adaptation of Little Women truer to Alcott’s time, nestling us closer to the book’s homey, Protestant values.

Works Cited and Consulted

Alcott, Louisa May. Little Women. 1868-69. Edited by Valerie Alderson, Oxford UP, 1998.

Alderson, Valerie. Explanatory Notes. 1994. Little Women, by Louisa May Alcott, Oxford UP, 1998, pp. 474-89.

Little Women. Directed by Gillian Armstrong, Columbia, 1994.

Little Women. Directed by Greta Gerwig, Sony, 2019.

Merrill, Frank T., illustrator. Little Women, by Louisa May Alcott, Roberts Brothers, 1880.

The author, a professor of literature, has written and published this blog post for educational, critical, and analytical purposes. All images are included only to bolster the post’s argument and to further its educational purpose.