Parents aren’t supposed to have one child they like more than the others, but what about authors? Many writers must have, at least for some of their books, a favourite among their fictional progeny—a character of which they’re not only especially proud but fond.

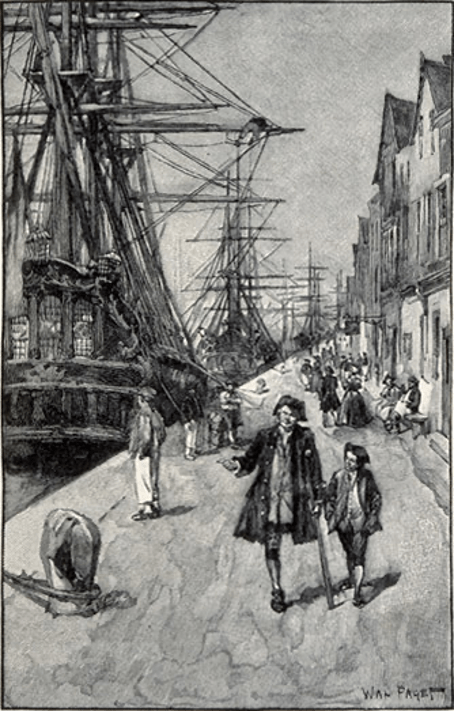

The stand-out (on one leg) character in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883) is Long John Silver. He’s introduced to us, via letter, by the slightly foolish, credulous Squire Trelawney, who calls him “a man of substance” and speculates, with what seems like more than passing racism, that it is Silver’s wife, “as she is a woman of colour”, who “sends him back to roving”. That “roving” will be launched on the Hispaniola, taking Captain Smollett, Trelawney, Dr. Livesey, Jim Hawkins, and their crew of hired hands, with Silver as the cook, to the treasure on the map that Jim took from the murdered Billy Bones’s sea chest in his mother’s seaside inn.

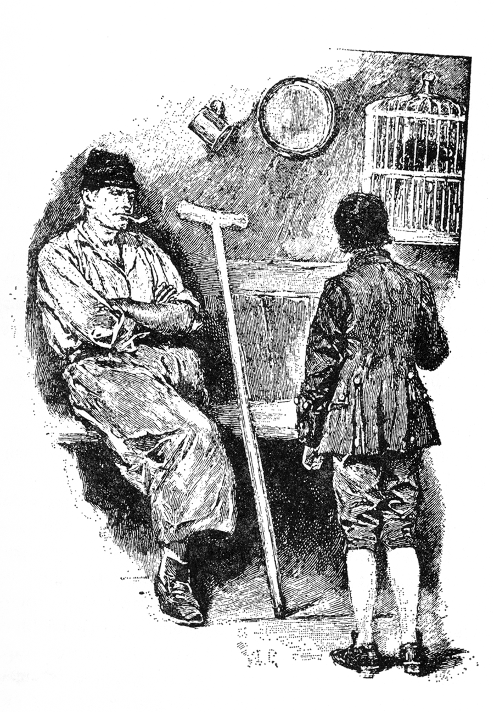

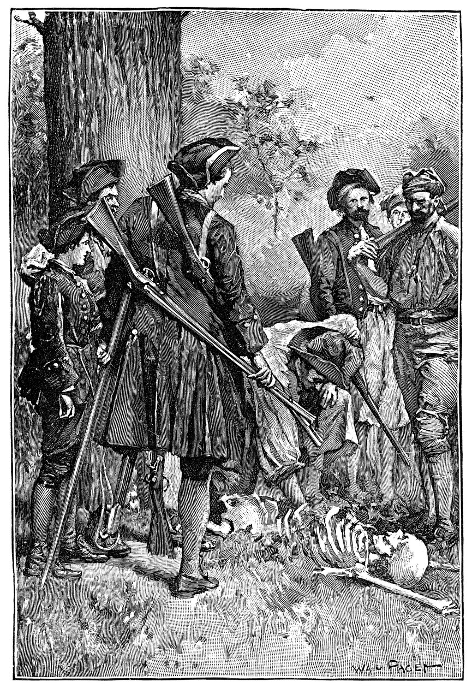

Jim, concerned that Silver could be that dreaded “one-legged sailor” whom Bones once told him to watch out for, upon first meeting Silver finds him to be a pleasant, affable fellow. But soon, aboard the ship, hiding in an apple barrel, he overhears the peg-legged plotter’s plan to kill Smollett, Trelawney, Livesey, and co., and split the treasure with his fellow mutineers. Then, on the island, from a hiding-spot he sees, to his horror, just what Silver is capable of:

With a cry, [Silver] seized the branch of a tree, whipped the crutch out of his armpit, and sent that uncouth missile hurtling through the air. It struck poor Tom [an honest hand], point foremost, and with stunning violence, right between the shoulders in the middle of his back. His hands flew up, he gave a sort of gasp, and fell.

. . . Silver, agile as a monkey, even without leg or crutch, was on the top of him next moment, and had twice buried his knife up to the hilt in that defenceless body. From my place of ambush, I could hear him pant aloud as he struck the blows.

Silver, then, is a charmer, a dissembler, a schemer, a double-crosser, a mutineer, and a murderer. Yet we, like Jim, cannot look away, because he’s the adventure’s most fascinating character: so cool under fire, charming, devious, and wily. He’s the utterly compelling anti-hero who gave the book its original title The Sea Cook, who eclipses young hero Jim—questioning the basic notion of Treasure Island as a “boy’s book”—and who bothered some critics at the time, with more than one thinking the novel not “wholesome”. The unnamed reviewer in The Athenaeum felt that Silver should not have “got off”, that is, escaped Smollett, Hawkins, and co. when the Hispaniola docks at a port in Spanish America on the return home. Silver teaches Jim, and the child reader, that one seen anew as a “monster”—as Jim sees Silver on witnessing his murder of Tom—is very much a man, too. Silver acts fatherly to Jim and relies on him, more than once, to trust him, and Jim does see him as “twice the man” that the rest of the pirates are. And Stevenson leaves him out there, beyond the confines of the narrative, roaming and “roving” alive and free.

It’s Silver who, in Stevenson’s fable “The Persons of the Tale” (1895), steps outside the narrative, along with Captain Smollett, to take a smoke-break: “After the 32nd chapter of Treasure Island, two of the puppets strolled out to have a pipe before business should begin again, and met in an open place not far from the story.” In the novel, it’s Silver who, in his speech, warps and reshapes, as Emma Letley has noted, in a sign of distorted morality, our sense of “duty” as “‘dooty’”; “Deposed” is written in a Bible by the pirates as “Depposed”, which happens to emphasize how much Silver is posing, or acting; it’s the scoundrel of a sea cook who warps and reshapes our romantic sense of pirates, with his shiftiness, amorality, and roguish charm drawing us in as often as it appalls us. In “The Persons of the Tale”, a sly bit of metafiction with no comforting moral, Stevenson dives deeper into romance and fiction to more profoundly question reality, morality, and religion. Smollett and Silver talk of an “‘Author’” as if he’s God, but Silver’s point that “‘if the Author made you, he made Long John’” has us doubt God’s morality, especially since, as Silver declares, “‘if there is sich a thing as a Author, I’m his favourite chara’ter. He does me fathoms better’n he does you—fathoms, he does. . . . he’s on my side, and you may lay to it!’”. What does it mean when the darkest character is also the deepest, most enthralling, and, here, most self-aware (“‘I’m on’y a chara’ter in a sea story. I don’t really exist.’”)?

In his inimitable way, then, Stevenson’s favourite—and one of literature’s great villains—not only rends asunder any reassuring, escapist notion of a “boy’s adventure story” but turns the book into an anti-heroic anti-romance. (He is a darker reflection of Jim, whom he calls “‘the picter of my own self when I was young and handsome’”.) After all, when Silver escapes, at the end of the novel, taking a sack of coins with him, no-one wishes to pursue and re-capture him—they are mainly relieved that he’s no longer their concern: “I think we were all pleased to be so cheaply quit of him” (these are hardly heroes, then!). And it is largely because of Silver that Jim—who had “felt in this delightful dream” while “bound for an unknown island, and to seek for buried treasures!”—now, he remarks at story’s end, has his “worst dreams”, he tells us, “when I hear the surf booming about [Treasure Island’s] coasts, or start upright in bed, with the sharp voice of [Silver’s parrot] Captain Flint still ringing in my ears: ‘Pieces of eight! pieces of eight’”. The metallic-named Silver takes the shine off buccaneering for Jim and for us; it’s the beguiling backstabber and cutthroat who makes it so horridly, unforgettably clear that a pirate’s treasure is blood-money, not just ill-gotten but murderously won. As Peter Hunt notes, such critics as Alistair Fowler and Naomi J. Wood have pointed out the novel’s “connotation of corruption and debasement attached to silver in a [1700s] world moving to the gold standard”; even Jim, Hunt observes, reflects on the cost of the booty when he is sorting through it: “what blood and sorrow . . . what shame and lies and cruelty”.

And so LJS is RLS’s favourite because he is the high-wire character, more than any other in the author’s works, who reveals the electric current of realism through romance, the darkness running through fiction that only seems mere child’s play.

Works Cited

Hunt, Peter. Introduction. Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson, Oxford UP, 2011, pp. vii-xxxi.

Letley, Emma. Introduction. Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson, Oxford UP, 1998, pp. vii-xxiii.

Paget, Walter, illustrator. Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson, Cassell, 1899.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. “A Fable: The Persons of the Tale.” 1895. Appendix 2 in Treasure Island, edited by Peter Hunt, Oxford UP, 2011, pp. 192-94.

—. Treasure Island. 1883 [first book edition]. Oxford UP, 1998.

The author, a professor of literature, has written and published this blog post for educational, critical, and analytical purposes. All images are included only to bolster the post’s argument and to further its educational purpose.